Two tourism developments on the Red Sea coast, Amaala and the Red Sea Project, will not live up to claims of ecological sustainability. Both resorts will have dedicated airports, sending carbon emissions soaring and hardwiring fossil fuel dependency.

An aerotropolis of sorts, a tourism resort with its own dedicated airport, is emerging on the Red Sea coast of northwestern Saudi Arabia. Amaala is a planned tourism gigaproject covering 4,155 square kilometres of terrain on land and sea, with more than 2,500 hotel rooms and over 800 residential villas. On 26th June renderings for the terminal and control tower of a luxury airport to serve Amaala were unveiled by UK-based Foster + Partners.

Luxury and exclusivity characterise the three main components of Amaala: Triple Bay – a luxury wellness resort and sports facilities including golf, equestrian, polo and falconry; Coastal Development – a cultural district featuring a museum of contemporary arts, film and performance arts venue and a biennial park and The Island – one of the world’s ‘most exclusive enclaves’ featuring botanical gardens, artworks, sculptures and private residences surrounded by landscaping. Amaala aims to attract ultra-high net worth individuals (UHNWIs), specifically targetting the very wealthiest, ‘the top 2.5 million ultra-high net worth individual luxury travellers’. This really is high-end tourism; Amaala’s target market segment is the wealthiest 0.03 per cent of the world’s total population of more than 7.8 billion. The resort will have its own ‘special regulatory structure’ to attract the super-rich.

Taking premium tourism to new heights, Amaala’s own dedicated airport will be as luxurious as the resort. Chief executive of Amaala, Nicholas Naples said: the ‘gateway to Amaala…will be a unique space that personifies luxury and marks the start of memorable experiences for the world’s most discerning guests’. Scheduled to open in 2023, coinciding with opening of the first phase of the resort, Amaala airport will initially serve private jets and charter flights, before expanding to accommodate commercial airlines. When fully complete, by 2028, Amaala Airport terminal, a ‘spacious light filled courtyard’, will have capacity for 1 million passengers per year.

Zero carbon (but what about the flights?)

Listing a mutlitude of ecological features – including an organic farm, utilising biodegradable materials, preventing plastic pollution, protecting iconic species, renewable energy including solar fields, recycling, treating wastewater for use in agriculture – Amaala claims it will ‘set an example for sustainability and eco-conservation in the region’. CEO Nicholas Naples, said ‘energy requirements will be met by using renewable sources, with the entire Amaala development having a zero-carbon footprint’. All these laudable ecological measures will be undermined by the impacts of travel to and from the resort. Amaala will be heavily dependent on aviation; an estimated 80 per cent of visitors will arrive by air. Flying is the most carbon intensive mode of transport and the carbon footprint of travelling by private jet is far higher than comparable journeys by commercial airliner; some estimates quantify the differential at 10 times the amount of carbon per passenger.

Foster + Partners’ design for Amaala Airport, a ‘sleek mirrored edifice’ inspired by ‘the optical illusion of a desert mirage‘, received a lot of publicity. The angular, shiny roof is indeed striking but its just an ostentatious example of superficial architectural flourishes that are typical of airport design, a fancy veneer disguising a functional concrete box. Gerard Evenden of Foster + Partners said: “The passenger experience through the entire building will be akin to a private members club … The design seeks to establish a new model for private terminals that provides a seamless experience from resort to airplane”. Passengers will be enclosed in a bubble sealed off from the real world. Damaging environmental impacts of emissions from private jets will be externalised, inflicted on other people, predominantly the poorest, living elsewhere and in the future. As less privileged people contend with extreme weather private jets owned by UHNWI’s parked at Amaala will be protected from the slightest climactic variation, in climate-controlled hangars.

Architects criticise Amaala Airport

In Architects Journal, Greg Pitcher queried whether Foster + Partners’ involvement with the Amaala airport project aligned with the firm’s carbon reduction pledges, in particular commitment under the Architects Declare banner to ‘evaluate all new projects against the aspiration to contribute positively to mitigating climate breakdown’. Sustainability expert and consultant Simon Sturgis said: ‘These sort of projects suggest that Foster + Partners is still engaged with 20th rather than 21st century thinking … This represents a climate betrayal’. Another consultant, Robert Franklin, weighed in on the Architects Declare movement, describing it as ‘a calculated, cynical insult to anyone who understands the lease nuanced interpretation of sustainable’.

Architects Climate Action Network (ACAN) polled network members asking them about their thoughts on Foster + Partners’ involvement in Amaala Airport. A clear majority opposed the scheme and ACAN wrote an open letter to voice concerns, arguing that architecture practices working to expand aviation goes against pledges to ‘Evaluate all new projects against the aspiration to contribute positively to mitigating climate breakdown’. ACAN also questioned how the airport project could be reconciled with Foster + Partners being a signatory of Architects Declare commitments recognising rapid decarbonisation as a global imperative.

Superyachts and luxury cruises

For those arriving at Amaala by sea there will be facilities for yachts, specifically ‘luxury yachting’. Naples spoke to Superyacht News about Amaala. Explaining that Amaala is part of a ‘yachting strategy for the Red Sea’ whilst acknowledging that while ‘yachting and environmentalism often aren’t seen to go hand-in-hand’ he was ‘confident that the project will be considerate to its surroundings’. Such confidence is unwarranted as travellers on superyachts, luxury vessels with price tags upwards of $100 million, leave ‘oversized personal carbon footprints‘ in their wake. The carbon footprint of one Superyacht, Venus, the result of 51,796 kilometres travelled in 2018, was estimated at 4,571 tonnes. This astonishingly massive figure is 279 times the average Australian citizen’s annual carbon footprint – for all their activities, not just transportation – and 594 times the average Chinese citizen’s carbon footprint.

Amaala will also be a calling point for boutique luxury cruises. Each passenger on board these boats will wield an even larger carbon footprint than the thousands of people crammed on board cheaper vast cruise ships that resemble floating cities. And Amaala’s facilities for arrivals by sea, marinas to accommodate international races and regattas, are likely to have negative environmental impacts on the pristine Red Sea coastal ecosystems. Large concrete structures and air and water pollution from boats could compromise biodiverse ecosystems that provide havens for whales, turtles and healthy coral reefs.

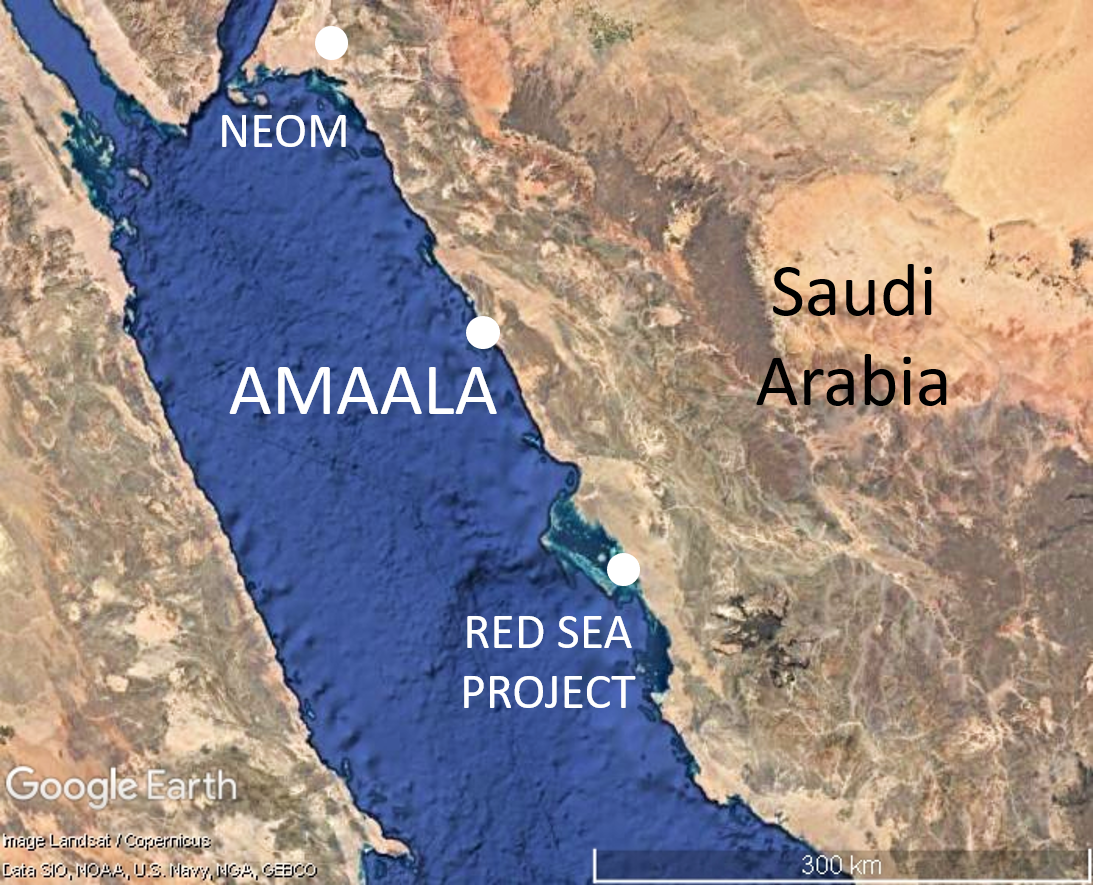

Neom megacity and the Red Sea Project

Amaala is situated between two other developments on the Red Sea coast: Neom megacity to the north and the Red Sea Project to the south. Vivian Nereim and Donna Abu-Nasr reported for Bloomberg on their visit to Neom in July 2019. They explored an eminently desirable setting for development, an area blessed with ‘stunning untouched shorelines with waves rippling in the turquoise water’ against a backdrop of purple volcanic mountains. Residents were uncertain and divided over whether benefits from Neom megacity would accrue to them: ‘Many of the locals who have lived there for years are looking forward to some prosperity, while others are concerned they will be removed and their homes bulldozed.’ Rumours swirled of large-scale resettlement to make way for luxury villas and office complexes and Neom stated that under current estimates more than 20,000 people would be moved. Megaprojects including a ‘huge port’ and a causeway to Egypt were in the works. A small airport serving Neom opened in June 2019.

The massive Red Sea tourism project, comprising resorts on 22 islands and six inland sites, will, like Amaala, be served by its own dedicated airport. In July 2020 infrastructure contracts for Red Sea International Airport were awarded to two Saudi firms: Nesma & Partners Contracting and Almabani General Contractors. And Foster + Partners is also involved in the airport. In July 2019 the firm was awarded the design contract. As with Amaala airport a whimsical architectural facade will evoke the surroundings, ‘the form of the roof shells is inspired by the desert dunes’.

Although not built for private jets the ‘design of the terminal aims to bring the experience of a private aircraft terminal to every traveller by providing smaller, intimate spaces that feel luxurious and personalised’. Visitors will be funnelled from the airport to the resort via ‘an immersive experience of the highlights at the resort’ in a Welcome Centre and ‘departure pods’ with spas and restaurants. Red Sea International Airport’s projected number of air passengers is identical to Amaala airport: 1 million per year. And the emphasis on environmental policies, such as zero waste-to-landfill and ban on single-use plastics, is similar to Amaala. Red Sea Project developers ‘want it to become one of the world’s most succussful sustainable tourist resorts’. Visitors will be given personal carbon footprint trackers to encourage them to think about sustainability. If these trackers were to include flights visitors would see their carbon emissions exceeding that of the majority of the worlds’ people who have never flown, before they even step off the plane into the luxury terminal.

A New Civil Engineer article, proclaiming the airport to be ‘eco-friendly‘, states that ‘the entire infrastructure of the Red Sea Project, including its transport network, will be powered by 100% renewable energy’. Conversion of transportation systems is one of the most difficult aspects of transition to renewable energy. Flights powered by renewable energy are not even remotely on the horizon. Much-hyped biofuels only provide a minute proportion of aviation fuel, just 0.01 per cent. Scaling up aviation biofuel production would destroy forests and other ecosystems and trigger land grabbing for plantations. Many airports have installed solar panels on unused land surrounding runways, providing a proportion of the power requirements for ground operations. But solar flight is a distant dream. The only solar-powered planes to successfully fly long distances, Solar Impulse 1 and 2, carry just one or two people at speeds rarely reaching 100 kilometres per hour.

Like Amaala, Neom and the Red Sea Project are supported by the Public Investment Fund KSA (PIF), Saudi Arabia’s sovereign fund, and all three projects are part of the Saudi Vision 2030 programme. Spanning various sectors including tourism, real estate and entertainment Saudi Vision 2030 aims to diversify the economy away from dependency upon oil. Tourism is a prominent sectoral focus, anticipated to increase from the current 3 per cent of gross domestic product to 10 per cent by 2030. Yet Amaala and the Red Sea Project, flagship tourism developments, are heading in the opposite direction from reducing dependency on oil. Dedicated airports serving these two resorts might not draw upon Saudi Arabia’s depleting oil deposits. But both facilities will require prodigious amounts of oil extracted from somewhere.