An alliance of community and environmental organizations, led by TechnoparcOiseaux, works to protect the highly biodiverse Technoparc Montréal wetlands, north of Montreal-Trudeau Airport, from development. There is widespread support for conferring protected status to the welands through inclusion in a national urban park.

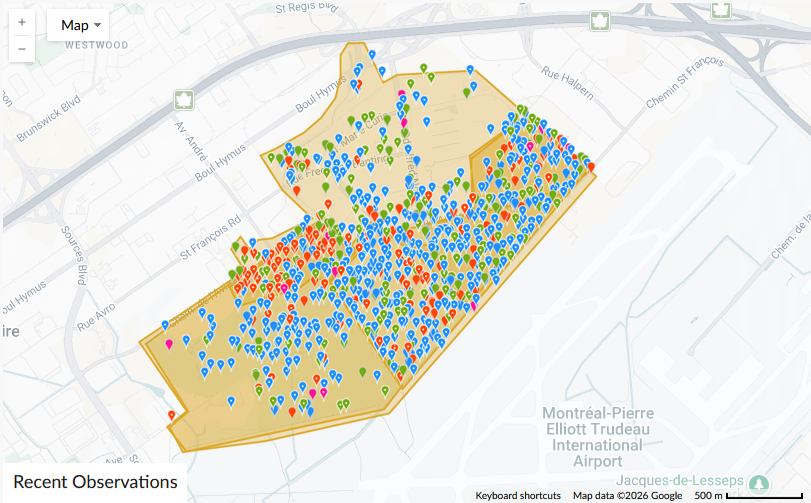

Technoparc Montreal, a high-tech industrial park near Montreal-Trudeau International Airport, is situated in the most biodiverse wetlands on Montreal Island, known as the Technoparc wetlands. Many citizens’ observations of plant and animal species are recorded on the Technoparc:Montreal Wetlands section of the iNaturalist crowdsourced identification system. By March 2026, 17,929 observations of 1,302 species by 549 observers had been recorded. But there is a long history of encroaching development which has been opposed at every stage. In July 2016 conservationists urged Technoparc to reconsider development of Eco Campus Hubert Reeves, for cleantech startup companies, on an area of the wetlands containing a marsh hosting a wide variety of birds; 160 species had been spotted. Bird Protection Quebec said development on the Technoparc wetlands, ‘an oasis in the heart of Montreal’, posed threats to uniquely biodiverse wetlands and woodlands, with the number of bird species among the highest in the Montreal region and including 19 categorized as threatened. Les Amis du Parc Meadowbrook passed a resolution, endorsed by Green Coalition and Sauvons la Falaise, calling on authorities to impose an immediate moratorium on Technoparc Montreal expansion and to consolidate undeveloped areas into a protected wildlife refuge. Extension of a road into the wetlands continued despite the presence of a few least bitterns, a small species of heron thought to be at risk in the Montreal area, leading members of the Green Coalition, Sauvons la Falaise and the Green Party to hold a news conference at the site.

In March 2018 Joel Coutu, leading birders on regular walks in the wetlands drew attention to Red-shouldered hawks, merlins and other birds of prey, indicating a richly biodiverse environment and mammals including coyotes, foxes, beavers rabbits and skunks. Bird enthusiasts and environmental groups intensified pressure to preserve the wetlands in August 2018 with a petition demanding a halt to works on sensitive areas in and around the Technoparc and to protect the sites as a ‘Sources Nature Park’ conservation area attracting over 68,000 signatures. Bird species nesting on the site that activists were concerned about included four at-risk species: Least Bittern, Wood Thrush, Eastern Wood-Pewee and Barn Swallow. Tree cutting for a Réseau express métropolitain (REM) light metro station at the Technoparc began in September 2018. TechnoparcOiseaux, Trainsparence and Montreal Climate Coalition had led a legal attempt to halt the project, appealing a previous lawsuit demanding a halt to the works that had been thrown out, but the provincial government had passed a special law enabling its construction. Matthew Chapman, president of Montreal Climate Coalition, said, “The biggest project in the last half century went forward in a very undemocratic way” and that it would facilitate development eroding the area’s remaining green space. The previous month, environmentalists had noted the irony of Eco-Campus Hubert Reeves being named after a renowned ecologist and astrophysicist, as preparation of the site included removing 3,000 trees for extension of a road anout 500 meters into natural space.

In September 2021, while Covid-19 restrictions were in place, dozens of local residents gathered near the Technoparc in a demonstration organized by TechnoparcOiseaux, protesting a proposed 15,000 square meter facility for production of surgical masks on part of the wetlands called Monarch Field. Efforts to expand the Des Sources Nature Park to include the Technoparc wetlands received a setback in February 2025 when Aéroports de Montréal (ADM), operator of Montreal-Trudeau Airport, stated concerns over bird strikes in the aftermath of a 29th December 2024 air crash in South Korea in which 179 people died. Air accident investigations had concluded that bird strikes were a factor and ADM stated, “It is inconceivable to ask an airport authority to assign a nature park use to such a large land located so close to the airfield and runways, as it would increase the presence of wildlife on site.” Katherine Collin of TechnoparcOiseaux rejected this argument saying, “We believe that ADM is overstating the dangers posed by the bird population here”. John Gradek, an aviation expert, said ADM was being too cautious as it can deploy technology such as blank cannons, along with falconry, to control birdlife around the airport.

ADM said it planned to develop a “decarbonization support center” on part of the land, Lot 20, in the following 10-20 years, claiming that any development of the site would protect areas that are of high ecological value and safeguard endangered species. Its 2023-2043 master plan includes solar panels, storage for ‘fuels of the future’ and other development on the site and the adjoining Dorval golf course. TechnoparcOiseaux’s Katherine Collin said, “What we see is worse than we imagined. Development is planned over vital habitat for endangered and threatened species, there are no buffer zones planned around current conservation areas, there will be a massive loss of green space – 130 hectares.” At ADM’s May 2025 annual public meeting president and director general, Yves Beauchamp, said the primary concern was passenger safety, “So a park of this expanse, near the runways, is not compatible with the safety goals we have. So will we change our opinions? No.” Yet hopes that the federal government might select the lands north of Montreal-Trudeau Airport as a national urban park, conferring protected status on 200 hectares of green space, were raised by a letter from the minister responsible for Parks Canada, Steven Guilbeault, stating, “The federal government is open to creating a national park on those lands”. A letter to Transport Minister Steven MacKinnon from Communauté métropolitaine de Montréal (CMM) executive director Massimo Iezzoni and Montreal’s executive committee chai Émilie Thuillier stated, “Few subjects enjoy such unanimous support within the CMM as the importance of protecting the natural areas around Montreal-Trudeau International Airport” and pointed out that the CMM represents 82 municipalities and 4.3 million people, nearly 50 per cent of the population of Quebec’s population.

For more information including references for all source material, photos and videos see the case study on EJAtlas, the world’s largest, most comprehensive online database of social conflict around environmental issues – Technoparc Montreal wetlands, Quebec, Canada