A study focussing on three villages affected by land acquisition for expansion Mohali Aero City, southwest of Shaheed Bhagat Singh International Airport, raised concerns over threats to rural livelihoods.

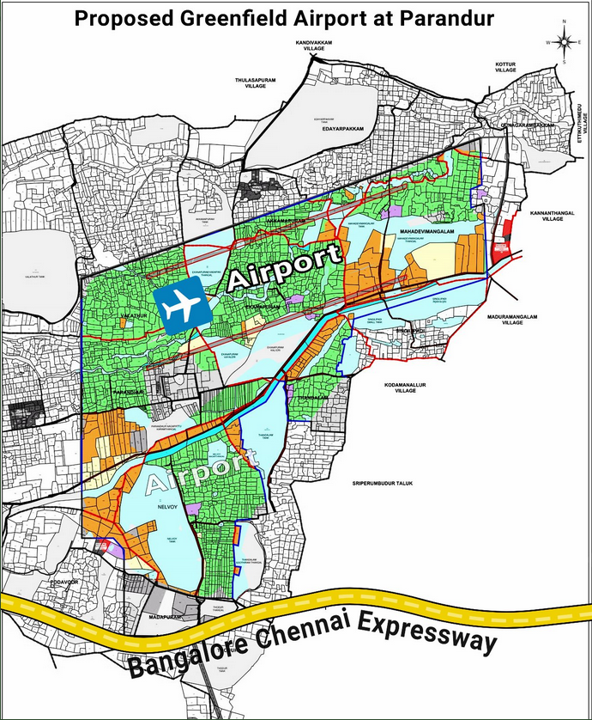

Proposed acquisition of 5,438 acres (2,200 hectares) of land from 14 villages – Bakarpur, Naraingarh, Kishanpura, Safipur, Rurka, Matran, Bari, Chatt, Saini Majra, Seon, Kurari, Chau Majra, Manauli and Paton – for AeroCity expansion, called ‘Aerotropolis’, was confirmed by Greater Mohali Area Development Authority (GMADA) in 2017. A 2021 article in the Journal of Land and Rural Studies by Thomas Reuter, Sarbjeet Singh, A.K. Sinha and Shalina Mehta, Land Grab Practices and a Threat to Livelihood and Food Security in India? A Case Study from Aerocity Expansion Project from S.A.S. Nagar, Punjab, analyses the project as an example of large-scale acquisition of highly fertile agricultural land. The authors describe ‘blatant land grab practices by the state authority in the name of development, which act as barriers to the food security and threaten the livelihoods of those whose land will be acquired’. The study focussed on three affected villages – Patton, Kurari and Seon. Fieldwork conducted in April 2019 included in-depth interviews with 50 displaced farmers.

Impacts on marginal rural people

A consolidated demographic profile of Patton, Kurari and Seon from the 2011 census showed that the total number of affected people was 3,031. A significant number, 955, belonged to the scheduled caste population, the most marginal rural people, many of them landless labourers, some of whom farm on leased land and other providing menial services. Land acquisition renders them homeless and they receive no compensation. The scheduled caste community of Patton village were marginal farmers owning only 1-2 acres of land. Scheduled caste people of Kurari and Seon did not own any land and depended entirely on agricultural activities. The working population was divided into two categories. ‘Main workers’ included marginalised individuals regularly hired by affluent farmers to work in their fields and people engaged in pastoral activities in a more favourable economic situation. ‘Marginal workers’ comprised migrant workers primarily from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar along with seasonal workers from other states coming to the area for work harvesting paddy and wheat. Agriculture was the primary economic activity in the three villages. Several farmers had modern equipment such as tractors, tillers and adequate irrigation with tube wells for which free electricity was provided by the state. Farmers getting cash compensation for surrendered land tend to lose these subsidies, along with minimum price support for cereal crops.

Narratives from three affected farmers

The article includes narratives from three farmers affected by land acquisition for the Aero City Expansion. A 59-year old man from Kurari village grieved that the pace of urbanisation would convert lush green fields into a concrete jungle. He worried that wheat, rice, maize and other cereal crops would disappear. GMADA and private builders offered different compensation packages, causing friction among those surrendering prime agricultural land and also between farmers and the state, resulting in litigations and delays in land acquisition and launch of construction activities. A respondent from Patton said that a decade ago the land was unsuitable for farming and nobody wanted to settle in the village. Residents worked hard and within two years had made all the available land suitable for agriculture. Most farmers grew vegetables and cereals which they sold at nearby farmers’ markets. When GMADA notified the village for land acquisition for the Aero City Expansion project farmers feared compulsory acquisition and sold their land to private builders. He said that when the government acquires land compensation is inadequate and the payment process often gets trapped in legislation. He had worked hard on the land he was forced to sell and was unsure of the productive capacity of new land he had purchased. A Seon villager whose land was acquired by GMADA for the Aero City Expansion had not been paid adequate compensation. He retained six acres but there was a possibility this would also fall under the proposed land acquisition, leaving him without any means of livelihood.

Loss of pastoral activities and social stability

Livestock provided an important subsidiary source of income in the three villages. Cows and buffalo were reared mainly for milk and cows also for manure. Pastoral activities in the three villages were mainly pursued by women waking up early to milk cows and buffalo. Land acquisition can deprive women of this primary economic activity making them far more vulnerable, especially when they run single-parent households. The case studies suggested that animal rearing as a livelihood became unviable because land used for pasture was no longer in villagers’ possession. Loss of agricultural land can cause cessation of pastoral activities, as most displaced households are not compensated with sufficient land to accommodate dairy animals.

Residents of the villages were content with acquisition of small portions of land along roads as it brought them improved connectivity. But acquisition of their fertile land for development of housing for wealthy urbanites and creation of infrastructure in which they were not equal stakeholders left locals feeling cheated. Their lives were marked with upheavals and displacement threatened close-knit social networks. The authors conclude that the Aero City Expansion project was ‘an ambitious ideas but executed without due diligence and groundwork’. Land acquisition brought revenue to the state but measures to support the interests of local residents were inadequate. Urban planners failed to foresee the risks of social tensions and the Aero City epxansion led to social and political instability. The article warned of agricultural decline and the prospect of food insecurity.