A plan for an ‘eco-luxury and tourism project’ encompassing nearly half of Bugsuk Island is the latest of a series of projects triggering a 50-year struggle for recognition of ancestral land and water rights.

In 1974 indigenous Pala’wan, Molbog and Cagayanin people were expelled from Bugsuk Island, part of the Balabac Municipality off the southern tip of Palawan, the westernmost point in the Philippines. An article by Indigenous Peoples’ Rights International (IPRI), based on an interview with Jomly Callon, President of the Sambilog-Balik Bugsuk Movement (Association of Indigenous Peoples and Small Fishers from the Southernmost Tip of Palawan), an indigenous people’s group, outlines a 50-year history marked by projects, facilitated by a series of policy decisions, taking the place of agricultural and fishing livelihoods. The land was awarded to Danding Cojuangco, Chief Executive of San Miguel Corporation (SMC), one of the Philippines’ largest business and industrial conglomerates, who established a nursery for hybrid coconut trees. In 1979 Cojuangco, in partnership with a French businessman, Jacques Branellec, formed the Jewelmer International Corporation which established a pearl farm in ancestral waters. Sambilog was formed in the year 2000 in response to land grabbing and reducing access to fishing grounds, working to gain recognition of ancestral land and water rights. They made an application for a Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT) which has still not been approved by the government. Indigenous people’s access to traditional fishing grounds was eroded further in 2005 when, without consulting indigenous people, the Balabac municipality was declared a ‘protected marine eco-region’, prohibiting indigenous people from fishing in their traditional fishing grounds. In 2014, following Sambilog protests in Manila calling for return of their lands through the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program Extension with Reforms (CARPER) the Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) issued a Notice of Coverage over agricultural lands for distribution to the people of Bugsuk Island. But DAR did not implement its decision to return the land to those affected by displacement.

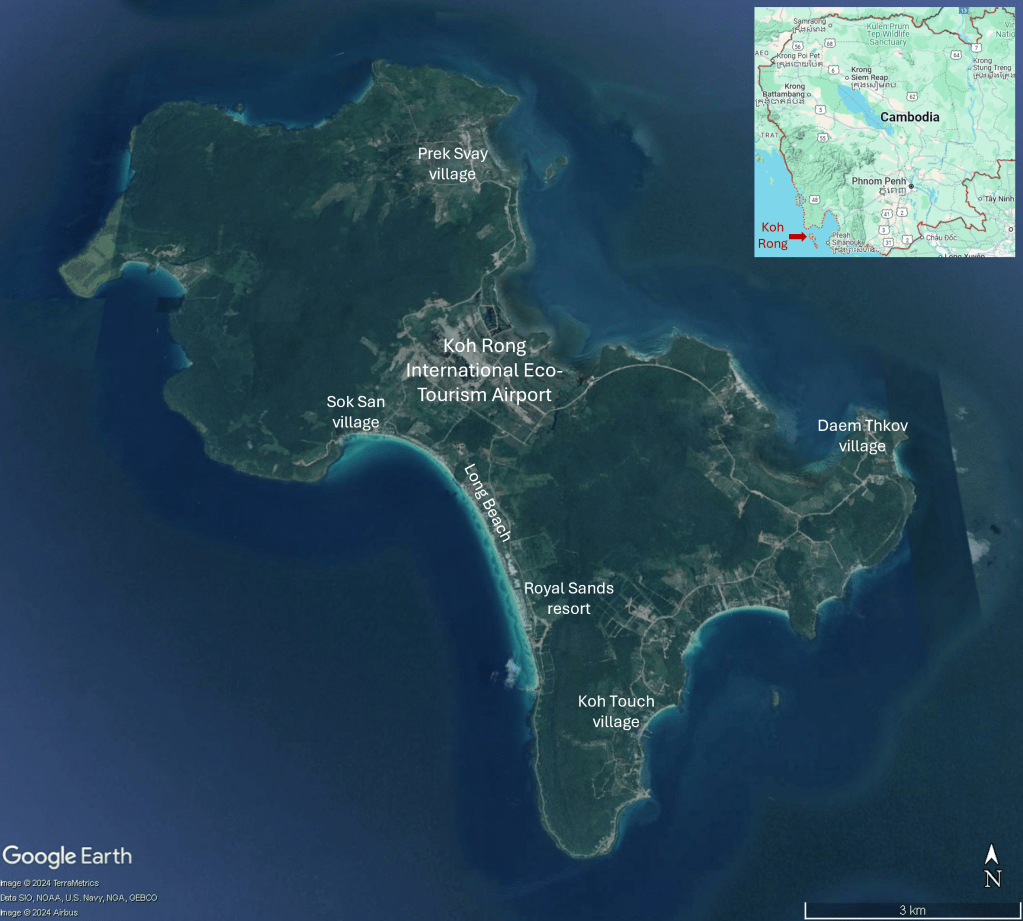

After Cojuangco’s death in 2020 Ramon Ang took up the role of CEO of SMC. Bugsuk Airport (also referred to as Bonbon Airport) was built by SMC to support the coconut plantation. In February 2022 Jose Alvarez, Governor of Palawan, speaking about Bugsuk Airport and a Philippine Air Force (PAF) facility in Barangay Catagupan being ‘crucial to the transformation of Palawan’s southernmost region as a new tourist haven‘, said the coconut plantation had failed but that Bugsuk Airport was still under development with the runway already operational and used by people travelling to Balabac. Satellite imagery of Bugsuk island shows Bugsuk Airport, an airstrip near the southern tip of the island that is being developed for the PAF and a helipad. In 2023 the DAR revoked the Notice of Coverage that was issued in 2014 and under which the land would be returned to its original owners. The reason given for the cancellation was that the area is unsuitable for agriculture. Callon, countered this, explaining that residents were cultivating the land, growing many types of vegetables and fruit trees.

Environmental Impact Statement and Master Plan for resort taking up half the island

Bricktree Properties Inc., a subsidiary of SMC, plans to construct various so-called ‘eco’ tourism facilities surrounding Bugsuk Airport. Bricktree’s presentation at a public scoping event held in Bugsuk Community Center, Bugsuk Island on 25th May 2023 contains a timeframe for 2023-24 which includes access road clearing and construction, tree cutting, land clearing, construction of campsites, perimeter fencing and soil compaction. A number of ‘identified environmental impacts’ includes ‘Land tenurial issues and incompatibility with existing land use’, ‘Potential lost (sic) of fish related livelihood and conflict on the access/navigation of locals’ along with potential changes in water quality, water competition and dust from land clearance. The Environmental Impact Statement Summary for the Proposed Bugsuk Island Eco-Tourism Development Project, prepared for Bricktree, contains maps of the proposed site and a Proposed Master Plan comprising serveral zones taking up much of the south of the island along with a port on the northern tip.

The Environmental Impact Statement Summary states ‘The Proposed Project aims to be an eco-luxury leisure and tourism destination governed by sustainable development principles’. A project schedule from 2023 to 2038 is indicated. The project location spans two barangays (districts) – Bugsuk and Sebaring – and the estimated total project land area is 5,567.54 hectares (nearly half of the 11,900 hectare island). Supporting infrastructure plans include power generator, solar farm, water supply primarily from Bugsuk River Lagoon, wastewater and sewage management, telecommunications, materials recovery facility, landfill and beach front maintenance on the Bonbon beach shoreline. The area earmarked for structures, roads and other facilities is 1,141.84 hectares, with the remaining 4.425.7 hectares consisting of areas for future development, open spaces and leasable space. A map of the Proposed Master Plan shows various zones centred around the airport and airport facilities and connected by a road network:

- Eco-tourism area immediately to the south of the airport

- Resort development on the southeast coast

- Two forest / tourism areas

- Four commercial areas

- Low density and high density residential areas

- Recreation area

- Light industrial area

- Employee facilities

- Agriculture zone

- An area for port facilities on the northern tip of the island

Tinig ng Plaridel, the official student publication of the University of the Philippines College of Mass Communication, challenged the statement in the document that resolutions endorsing the proposed project without objections were obtained from Barangay Bugsuk in September 2023, saying that hundreds of locals oppose the project.

Intimidation and harassment of Mariahangin residents

During the 1974 expulsion of indigenous people from Bugsuk Island the people of Mariahangin (also spelled Marihangin), a small 38 hectare island north of Bugsuk Island, resisted; the eviction was stopped and people remained on the island. But 50 years later Mariahangin residents say the presence of armed men is pressurising them to leave. On 27th June 2024 DAR officials arrived on Mariahangin, to inform residents that their homes would be demolished to make way for an eco-luxury tourism project covering over 5,000 hectares in Barangay Bugsuk. Just two days later, early in the morning of 29th June 2024 16 unidentified armed guards arrived on Mariahangin Island. On 13th September a group of indigenous people from Mariahangin Island arrived in Manila to campaign for land reform, the return of the 10,821 hectares of land awarded to Cojuangco in 1974, for the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples to process their CADT application and to raise awareness of the 50-year struggle. The group included an 18-year old witness to the presence of armed men in Mariahangin in June who said a man wearing black headgear and a black mask had pointed a gun at him.

SMC denied involvement in the shooting incident and stated it has no connection with anyone involved in the incident and does not own any property holdings on Mariahangin Island. Yet, as reported by Bulatlat, residents claim that SMC does have an interest in Mariahangin Island and, in 2023, presented families with a ‘resettlement programme’, increasing an initial offer to P400,000 (USD6,852) per family to leave their ancestral land. In September 2024 the Philippine Misereor Partnership Incorporated (PMPI), a network of more than 230 social development and advocacy groups, expressed deep concern over human rights violations faced by the Molbog and Palaw’an communities arising from a land grabbing case. Mariahangin residents’ representatives, supported by the National Federation of Peasant Organisations (PAKISAMA) presented testimonies to the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) reporting reported ‘alarming incidents, including threats at gunpoint to force them out of their ancestral lands and intrusive surveillance and intimidation that profoundly disrupt their daily lives and livelihoods’.

On 2nd December 2024, contradicting Bugsuk residents’ assertion of their land rights, SMC reiterated its stated legal ownership of 7,000 hectares of titled properties on Bugsuk Island, saying that the titles had been held since original issuance during redistribution of agricultural land in 1974, predating the 1997 Indigenous People’s Rights Act. Earlier that day, nine indigenous Sambilog leaders began a nine-day fasting and praying event outside the DAR headquarters in Quezon City to amplify the 50 year land struggle of indigenous Bugsuk Island communities. They pointed out that Mariahangin land is agricultural – seaweed farming is the main source of residents’ livelihoods, followed by corn cultivation – so therefore the land should be returned to them under the provisions of the 1998 Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Law which states that all public and private agricultural lands are encompassed by the coverage for distribution to the people. An ILC Asia (International Land Coalition) statement in support of the seaweed farmers of Mariahangin Island raises concerns over loss of mangroves in a country particularly vulnerable to climate disasters and notes that mangroves on Bugsuk Island have already been cleared to make way for a 20km white sand beach.

In February 2025 Mariahangin residents refuted government dismissal of their allegations of harassment, land grabbing and restriction of access to fishing grounds. Residents said police and people suspected of being SMC representatives attempted to enter the community on 18th and 20th November and that armed guards had been stationed about 500-500 metres from Mariahangin. One resident said, “People there can barely earn a living because they’re constantly guarding against those armed men at the edge of the island.” Residents guarding the area reported threats from armed guards. Fishermen said guards were blocking access, seizing their equipment nad harassing them, with some being hit with paddles and illegally detained. One fisherman said his boat had been destroyed. On 5th March 2025 The Guidon reported that eight Mariahangin residents had been subpoenaed over allegations of assault and an individual received a subpoena for alleged cyberlibel. residents described these legal proceedings as part of “a pattern of relentless harassment” amidst their long-running land dispute with SMC over ancestral land on Bugsuk Island.